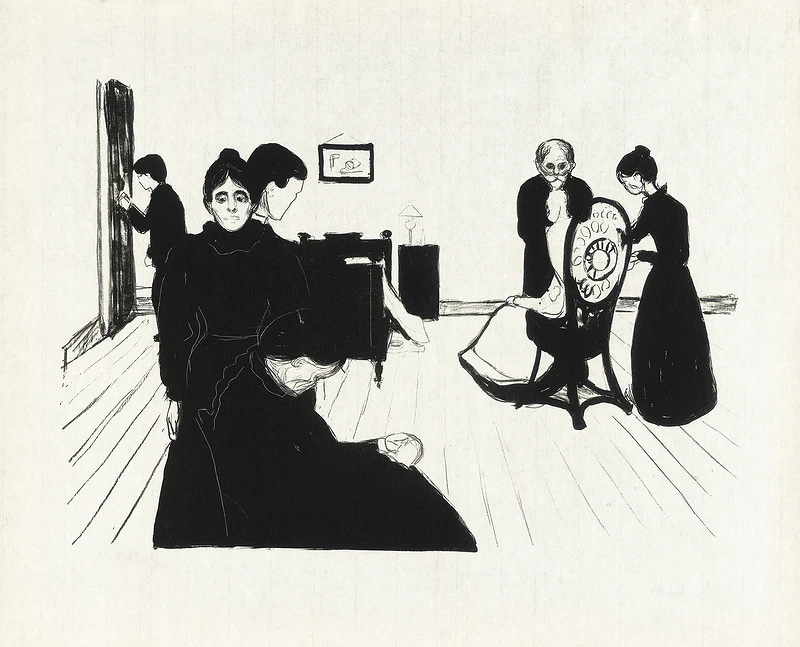

Death in the Sickroom (1896) by Edvard Munch. Original from The Art Institute of Chicago. Public domain.

Thomas reaches blindly, grasping for someone or something. I stoop to catch his hand. He turns toward me, slowly. His gaze is sluggish and empty. “Am I dying?” “Yes,” I reply, “but I am here with you.” I glance at the clock; it has been six hours since the ventilator was withdrawn. “Where is Delores?” His wife of fifty-eight years is absent from the bedside. She is uncomfortable in the shadows of suffering, so she sits in the waiting room wringing her hands over and over as if trying to squeeze life back into his body. “She will be here soon.” His face relaxes.

Another hour passes, then two. I revisit his room. I call his name and jiggle his shoulder. He does not rouse. I lean to glimpse his face. His milk-flecked pupils are rolled upward into hollow sockets of bone. He is teetering on the fringe, as close to death as death itself. I step outside the room and notice his wife pacing in the hallway. She is worn and weary, her brow furrowed, her lips grimaced. She approaches and opines. Thomas seems wedged between here and there, like a candy bar jammed in a vending machine. “How is he still living?” she laments. “He’s doing this on his time, not ours,” I respond. “But I think it will be soon.” She inquires if she can leave to take lunch, adding, “I want to be here when he passes.” I tell her yes, but advise she bring the food to the waiting room. She nods and disappears into an elevator. I retire to the computer room and scroll through charts. Shortly, a nurse enters and requests that I assess Thomas. She adds his wife is bedside, sobbing. I return to his room and stroke his arm. He is chilled, almost cold, the warmth already departing. I place my stethoscope on his chest. His lungs and heart are silent. I move to his wife’s side and cradle her shoulders; he has finally passed from here to there.